The Strenuous Life

Today’s post is inspired by one of my greatest heroes. He wasn’t a perfect man - he shot his neighbor’s dog just because it snapped at him once (his father had just died and he was a bit angry). But he was a passionate, vigorous man, and it’s on this aspect of his life I’m going to focus today.

But first, he says it best himself.

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.

This man is Teddy Roosevelt, and that quote is the Man in the Arena excerpt from his Citizenship in a Republic speech (highly recommended in its entirety).

And this is what he has to say about a strenuous life:

I wish to preach, not the doctrine of ignoble ease, but the doctrine of the strenuous life, the life of toil and effort, of labor and strife; to preach that highest form of success which comes, not to the man who desires mere easy peace, but to the man who does not shrink from danger, from hardship, or from bitter toil, and who out of these wins the splendid ultimate triumph.

What does he mean by this? Best to see the examples from his own life. He was weak and asthmatic as a child, and instead of embracing that and eschewing physical exertion, he tackled it head on and strangled it to death. He started exercising and took up boxing, much at the encouragement of his father.

And here I pause for a moment to honor his father, whom Teddy looked up to more than words can describe. From PBS’s transcript:

But asthma continued to ravage him. He was anxious and suffered from a recurring nightmare that a werewolf was loose in his bedroom. His desperate parents tried remedies recommended by the best doctors of the day. Theodore was dosed with a medicine to induce vomiting, made to swallow black coffee, even forced to smoke cigars. At one point, he noted in his diary, his chest was rubbed so hard “that the blood came out.” When he was 11, his father took him aside.

He said, “You have been blessed with a wonderful mind, but you have to build your body. You have to take charge of your body.” In a way– in a larger way, he was saying, “You have to take charge of your life.”

Determined to be worthy of his father, the sickly boy spent hours every day trying to build himself a new body, slowly “widening his chest,” his sister remembered, “by regular monotonous motion – drudgery, indeed.” His father even paid a professional coach to teach his son how to box, and every summer he took him on camping trips, hiking through Maine and the Adirondacks and around the Roosevelt summer home at Oyster Bay on the shore of Long Island Sound.

Sounds like an amazing father. In any case, Roosevelt mastered his asthma and became captain of his fate. After graduating from Harvard, his doctor advised him that because of his serious heart problems, he should take a desk job and eschew physical exertion. Roosevelt completely ignored that advice, and continued to box, hike, row, horseback ride, and play polo and tennis. Even as president, he continued to box until some guy knocked his retina out and blinded his left eye. Then he took up jujutsu.

Roosevelt’s story is marked with tragedy, suffering, grief, and ultimately the will to swallow the grief and achieve “that highest form of success which comes…to the man who does not shrink from danger, from hardship, or from bitter toil, and who out of these wins the splendid ultimate triumph”.

His father died when he was at Harvard.

Shattered, for months he poured out his pain and bewilderment in his diary. “How little use I am or ever shall be.” “If I had very much time to think, I believe I should almost go crazy.” Along the shores of Long Island Sound, he sought relief in the natural world and in ceaseless physical exertion. He ran, hiked, boxed, hunted, and swam, wrestled.

He rowed a boat across Long Island Sound and back in a single day – 25 miles. He rode his horse almost to death, and shot a neighbor’s dog just because it snapped at him. Then he fled to the Maine woods. “Oh, Father, my father, no words can tell how I shall miss your counsel and advice.” Many years later, when Theodore was president of the United States, his sister wrote, “He told me frequently that he never took any serious step or made any vital decision for his country without thinking first what position his father would have taken.”

When Theodore returned to Harvard, he kept up his furious pace. He joined nearly every club, began a book on naval history, and fought for the lightweight boxing championship of the school, which he lost.

He found the love of his life at Harvard, but it was most assuredly unrequited. Unfazed, he pursued her relentlessly until she consented to become his wife. They moved in together, lived in paradise and he moved relentlessly up the ranks in his political career. She became pregnant, and happy anticipation was on everyone’s minds. He was 25.

And then one day, he receives a telegram telling him his wife Alice has given birth to a beautiful baby girl. Flush with happiness, he then receives a second telegram.

He races home, finds his wife dying of kidney failure and his mother dying of typhoid fever. They both pass away within hours of each other on the same day.

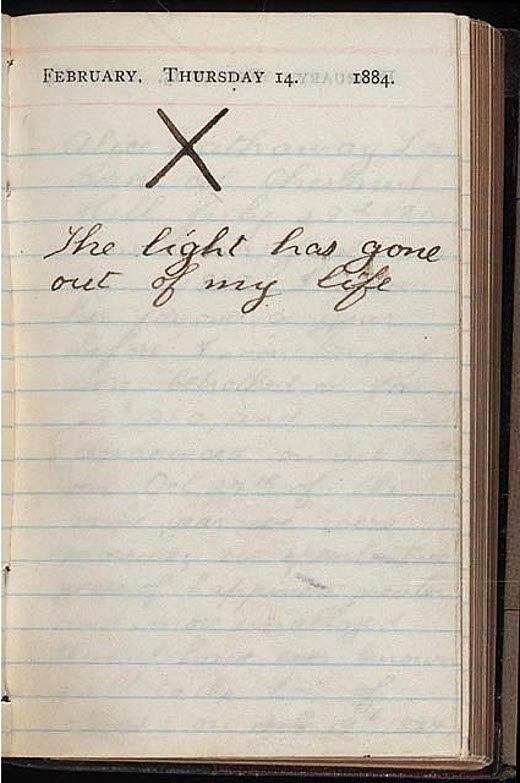

This is what he wrote in his diary that day.

He never mentioned his wife again. He abandoned his newborn daughter in the care of his sister, he abandoned his life, his career, and everything he had known, and rode west to the Badlands. He spent the next two years here, drowning out his sorrows through constant, feverish work and action.

An anecdote: As a deputy sheriff in the badlands, he hunted down three men who stole his riverboat, caught them, and guarded them singlehandedly for 40 hours without sleep so they could be brought back to town for trial.

In later life, he returned to politics and found himself appointed Assistant Secretary of the Navy, just moments away from rising to the very top and being Secretary of the Navy. Instead of keeping his comfortable loft and rising further in his career, however, he immediately resigned his post on the Declaration of the Spanish-American War, gathered a bunch of haphazard volunteers together, and shipped down to Cuba to fight on the front lines.

He quickly rose again to the rank of Colonel, and in the absence of any orders from superiors, urged his men to charge up Kettle Hill and San Juan Hill at the same time. He led the charge on his horse at the forefront of the advance on Kettle Hill. They captured both hills, and Teddy Roosevelt officially went down in history as an epic badass.

He is the only president to have ever received the Medal of Honor.

Later in life while campaigning under the Bull Moose Party, he was shot in an assassination attempt before he was slated to give an election speech. Instead of canceling his speech and having the bullet removed, he continued giving his speech for an hour and a half with blood seeping out of his chest.

Hell, he never got that bullet taken out. It remained in his chest for the rest of his life.

He died at the age of 60, after contracting a tropical disease and possibly malaria (for the second time, the first time being in Cuba) on a South American expedition through the jungle. He lost 50 pounds, became madly delirious, and had a fever of 103. He insisted that the expedition carry on without him, but ultimately his son managed to convince him to stay. He ultimately died of complications likely related to this expedition a few years later.

I doubt he regretted that much at all. This is one of the very few men who I truly believe wholeheartedly meant every vigorous word he expounded in his speeches. Actions speak louder than words, and I guess delivering a speech with a bullet lodged in your chest speaks pretty loudly. Being the youngest president then and now in the history of the US, the only president to have won the Medal of Honor, and to have become such a triumphant badass from such sickly and asthmatic beginnings - it really speaks something of a person.

At every moment in his long journey he faced every challenge head on and embraced the ideals of the strenuous life. Death does not faze a man who lives for something greater and believes in his principles. He could have died at so many instances during his life, and that was by intentional design.

What is a life without true risk? Without true challenge, true failure, without true ‘danger, hardship, and bitter toil’? What is a life that does not know great effort, great strain? For Teddy Roosevelt, perhaps, no life at all.

This man is the greatest embodiment of the will to power that I’ve yet seen. Thanks for showing us how it’s done.